Photo credit: Alan Vernon

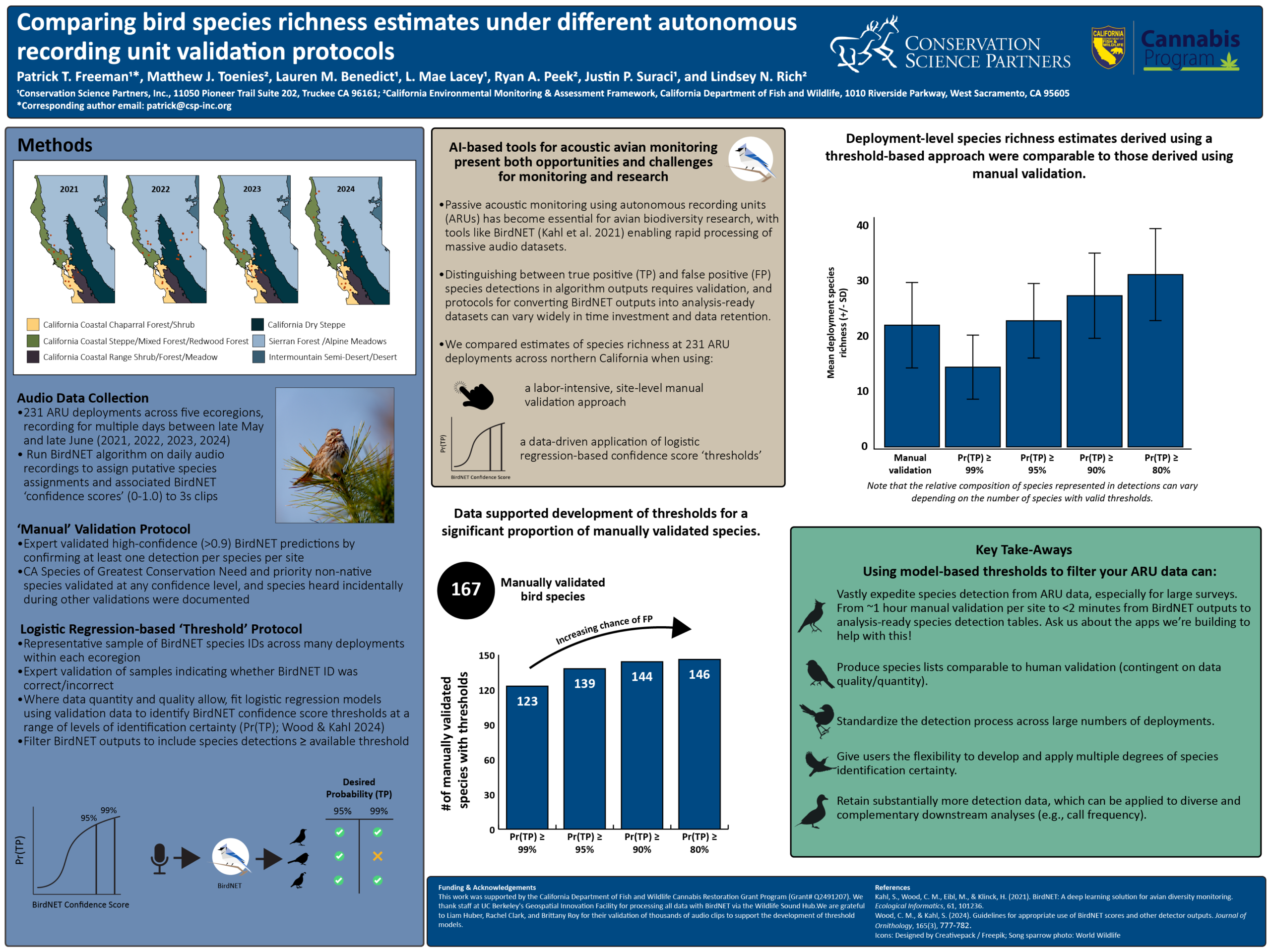

Over the last decade, autonomous recording units (ARUs) have emerged as powerful tools for monitoring avian biodiversity. But these devices generate mountains of data, mixing rare bird calls with trucks, footsteps, and fieldwork noise. Sorting through this audio data requires specialized knowledge and enormous amounts of time. AI-based tools like the BirdNET algorithm are now helping researchers process audio data more quickly and identify potential species detected in recordings. But the algorithm is imperfect. It assigns each detection a confidence score from 0 to 1, and distinguishing true positives from false positives still requires validation. Researchers face a conundrum: trust the algorithm and accept potentially erroneous species detections or invest more time manually verifying detections?

Over the last year, CSP scientists in the Changing Landscapes Lab have collaborated with California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (CDFW) Cannabis Program ecologists to tackle this challenge. Historically, the Cannabis Program used labor-intensive manual validation process to find true positive detections in BirdNET outputs from many sites statewide. To improve the efficiency of CDFW’s data processing, the CSP team developed a data-driven, statistical approach to identify species-level BirdNET confidence score thresholds for over 200 California bird species. These thresholds allow researchers to be, say, 95% confident a detection is real while saving hundreds of hours listening to audio clips.

Lead Scientist Patrick Freeman presented a new analysis using these thresholds at The Wildlife Society’s Western Section conference in Monterey in February. The analysis showed that site-level bird species richness estimates from the threshold method were comparable to those from manual validation—indicating the model-based approach could save valuable staff time without risking severe under- or over-counting the number of species present at a site. Freeman was thrilled to discuss how these methods could transfer to other projects as ARU use continues to rise. This work is part of a broader project evaluating how wildlife distributions have shifted over the last several decades and how they are likely to respond to future changes in climate and land-use.